With a two-story encircling verandah, the two and one-half story vernacular Shingle Style, balloon-frame First Colony Inn was constructed during the period of expanding tourism along the Atlantic Ocean in the 1920’s and 1930’s in conjunction with several other similar establishments.

Completely sheathed in shingles, the building now stands as the last original example of a traditional “beach-style” hotel genre that once graced the oceanfront at Nags Head. It is the oldest in continuous operation as a hotel, and has had food and/or restaurant service available under all but one management. The inn has always been the location for all types of organized social activities for guests and visitors alike and for many years was “the” place to dine. Its original proximity to dance halls, tourist and sight seeing activities, and the ocean assisted in securing its reputation as one of the most popular spots on the northern Outer Banks. The First Colony Inn History is a testament to Innkeepers preserving tourism in one of the most sought after vacation spots of the Eastern Coast of the United States.

The calm, peaceful atmosphere of the Outer Banks of North Carolina has attracted “mainlanders” since the turn of the nineteenth century. The long chain of narrow barrier islands that protects the North Carolina mainland was originally accessible only by regular steamer lines from Elizabeth City, Norfolk, and the Eastern Shore of the Albemarle Sound, or via private vessel. This geographic isolation and the accompanying social informality were the foundation blocks for a summer life-style that continued into the twentieth century.

Nags Head is one of North Carolina’s oldest coastal resorts. As early as the 1750s, people from the mainland came here seeking the healthy, rejuvenating effects of clean air and sea bathing of the islands. Because it did not experience the commercial and industrial development occurring in other coastal areas, Nags Head became “the” choice of summer vacationers. It was not until the early 1830s, however, that the area experienced significant development. It is said that the rapid growth of the community was started by a Perquimans County planter who purchased a parcel of land to build a summer residence for his family. When the house was completed, friends and neighbors from the mainland quickly decided they, too, wanted to escape the poisonous vapors and summer sicknesses believed to be prevalent in the swampy, low-lying inland areas.

As the numbers of vacationers increased, a need for public accommodations and organized summer entertainment developed. In 1838, in response to that need, the first hotel was built. It was constructed, like some of the first cottages, on the shore of the Albemarle Sound. By 1851 the facility had expanded to include over 200 guest rooms. It also boasted several detached guest cottages, a dining room and a ballroom, a general store, steamer wharf, and a boardwalk and tramway to the beach. Early hotel advertisements tempted visitors with promises of healthful and entertaining activities, and even offered steamer transportation. The summer community at Nags Head thrived in spite of the continued commercial development of the other coastal areas such as Beaufort and Morehead City. At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, however, the vacation spot was deserted by the mainlanders and the land belonged once again to the native Bankers.

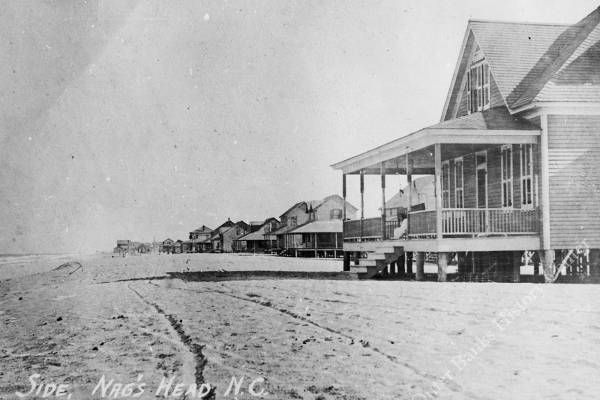

After the end of the war, the summer residents of Nags Head steadily returned. The summer of 1867 saw the construction of a brand new hotel, and Nags Head reportedly had never been so patronized. Before that time, most of the buildings of the family resort had been confined to the sound side of the island chain — vacationers reached the ocean via mule-drawn railroad cars. In the late 1860s, returning vacationers began moving their cottages to the ocean side, and new visitors bought property and built their cottages nearer the ocean. The first cottage actually constructed on the Atlantic Ocean was that of W.G. Pool, and dates from 1866.

Nags Head continued to experience slow but steady growth during the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, in spite of World War I. Following the intertwining periods of war and peace, dangerous tempests and placid waters, Nags Head, “the gay summer capital of Albemarle Society,” once more emerged as “the center of things” in the summers of the 1930s. A new paved road, connecting two new bridges at either end of the main island, allowed increased vehicular access and served to reinforce the development shift from the sound to the ocean side. One of the first commercial structures constructed on the ocean side, after completion of the Wright Memorial Bridge in 1930, was a dance hall called the Pirate’s Den. It was strategically located, along with several cottages, in a direct line from the east end of the new bridge at Kitty Hawk Beach. The hope was to attract mainlanders to purchase property along the Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately, the building burned down after only four or five years of operation. Following the demise of the Pirate’s Den, and a short-lived real estate venture at Virginia Dare Shores, the State flattened and widened the access road from the sound to the ocean. It was at that time that the business of tourism began to change the face of the Outer Banks.

The ocean side Nags Head of the 1930s closely resembled the earlier family resort of the sound side in social makeup. Women and children arrived during the week and were met by their husbands and fathers on the weekends. Those who could not spend the entire summer on the Outer Banks in their own cottages came for a week or two at a time, often staying in one of the several large hotels. On the sound side, the hotels had been social centers, where families vacationing in their own cottages gathered with friends for entertainment and social activities. The new hotels of the oceanfront fulfilled similar roles, providing not only accommodations and dining, but tourist services such as fishing trips and sailing and entertainment in the forms of dancing, bonfires and concerts for people of all ages. Days were alive with sunbathing, fishing, boating, and sightseeing; nights were filled with bowling, dancing and entertainment. Bedtime never came to Nags Head.

The Nags Head of the 1930s differed from that of the earlier resort in its steady growth and influx of modem conveniences for the tourists. Old cottages were expanded and new ones built. Filling stations for the newly arrived automobile sprang up and the Coast Guard station got a telephone. It was in this period of “progress” that the oceanfront hotels and establishments were built and promoted. They were all of simple wood frame construction, designed to be functional and serviceable without pretentious trimmings. Most were built on pilings and featured wood shingle siding and wood railings and shutters. Several also had open perimeter porches that allowed the capture of sea breezes and protection from the sun on a hot day.

The amenities provided at each establishment varied slightly. One, the Casino, was primarily a dancing and bowling hall with rooms upstairs, and Hollowell’s had a general store and post office on the first floor. Parkerson’s included a dining room, delicatessen, soda fountain, ladies’ restrooms and sleeping quarters for visitors. The Croatan and the Arlington were strictly for accommodations and dining, and the Nags Head Beach Club advertised series of well known dance bands.

Most of the early “beach-style” hotels no longer exist, but their names and memories still remain in the minds of those people who spent their summers there. Hollowell’s Hotel, built on the sound side by Graham Hollowell, was one of the first hotels relocated to the ocean side. It burned to the ground in the late 1970s. The Arlington, run by Cassey Morrissette, was also relocated from the sound side but was destroyed by a storm in the early 1980s. Parkerson’s, noted for its dance bands, burned in the 1940s, and the Wilbur Wright was damaged by a tornado and subsequently tom down. The Casino was demolished by its owner in the 1980s. Presently, there are only two remaining hotels from the 1930s zenith: the Croatan (partially occupied as a restaurant and no longer operating as a hotel) and LeRoy’s Seaside Inn (renamed First Colony Inn in 1937).

First Colony Inn (formerly LeRoy’s Seaside Inn) still has many Inn Amenities to this day.

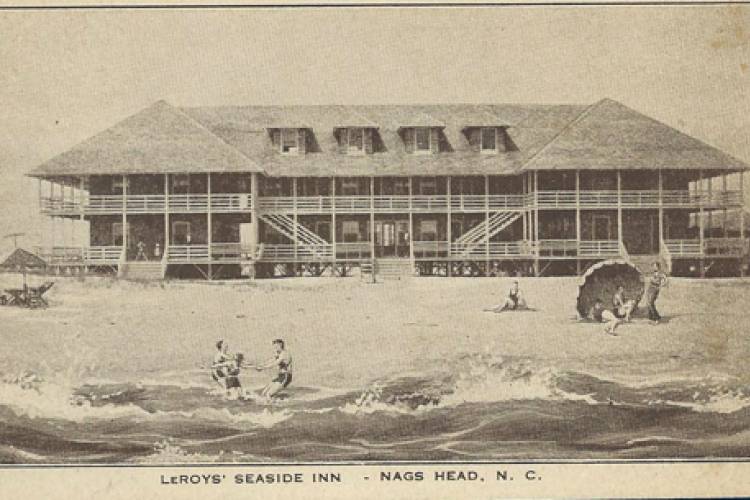

On January 18, 1932, Marie LeRoy purchased eight adjacent oceanfront building lots in Nags Head from Greenville, N.C. developer S.W. Worthington (George T. Stronach, trustee), in what was then known as the Stronach Subdivision. These lots were purchased for approximately $750.00 each. In February of that same year construction began on LeRoy’s Seaside Inn, which would be renamed First Colony Inn in 1937. (Previously, the LeRoys owned and operated the popular sound side LeRoy Cottage, which was built during the period preceding the ocean side development.) The LeRoys’ new hotel was built in the traditional style of Nags Head architecture — simple wood-frame construction, form and features dictated by climate and function, and utilization of readily available materials.

Lumber for Henry J. LeRoy’s new hotel was purchased from Kramer Brothers Lumber Company, one of the four largest lumber mills operating in Elizabeth City. Known for their manufacture of church pews, Kramer Brothers had an enviable reputation for using only the finest materials and performing excellent work. At the time, the success of the lumber mills had great influence on the building practices of the surrounding areas. The mill employed large numbers of men, producing great quantities of finished building products and manufactured items. Their location on the Pasquotank River served as a convenient departure point for the transportation of these items to such remote places as the Outer Banks.

Mr. Willis Leigh, an employee of Kramer Brothers who later married Mr. LeRoy’s daughter, Marguerite, played a significant role in the design of the hotel. He modeled the distinctive features of the hotel — the broad overhangs and sweeping roofline, the encircling breeze-catching verandahs, the protruding “Nags Head benches” incorporated into the simple slat railings — after the trademarks of Mr. Twine. It was this traditional functionalism that dictated the form and details of LeRoy’s Seaside Inn, as well as the other large hotels that sprang up along the ocean side in the early twentieth century.

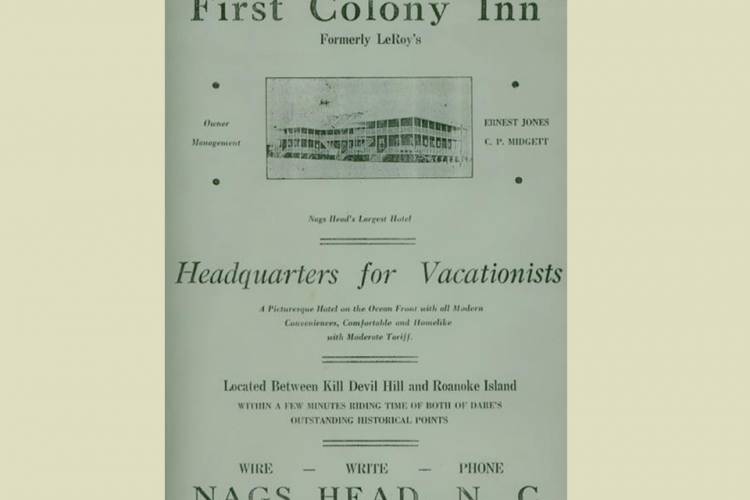

In April 1937, LeRoy’s Seaside Inn and its garage and outbuildings were sold to Capt. C.P. (Neil) Midgett and Ernest J. Jones, who changed the name to the First Colony Inn. Captain Neil and his wife Miss Daisy (Daisy Harrison of Currituck County) owned and operated the inn until 1961. During those twenty-four years, the First Colony Inn established itself as “the” place to be on the beach at Nags Head. Much of the inn’s reputation was derived from the restaurant’s cook, John White, who not only prepared the meals, but served as the night watchman and controlled many of the inn’s services. Miss Daisy, it is said, liked “big shots.” During the Midgetts’ ownership, such state celebrities as Lindsey Warren, Herbert C. Bonner and Melville Broughton (governor of North Carolina 1940-1944) stayed there. One of the “cottages” on the original site was known as the “governor’s cottage” because as many as five North Carolina governors spent time there. In addition, the First Colony Inn was the weekend retreat for many a businessman from Elizabeth City and Edenton, N.C., and Newport News and Norfolk, Va., whose family was staying at the inn for a week or more. Guests and relatives of nearby cottage owners also stayed at the inn during the peak vacation season.

Despite World War II, tourism at Nags Head (the oldest seaside summer resort on the North Carolina Coast) continued. Travel and vacations were curtailed somewhat and portions of the beach areas were blacked out, but by the summer of 1946, tourists began to pour across the Albemarle Sound once more.

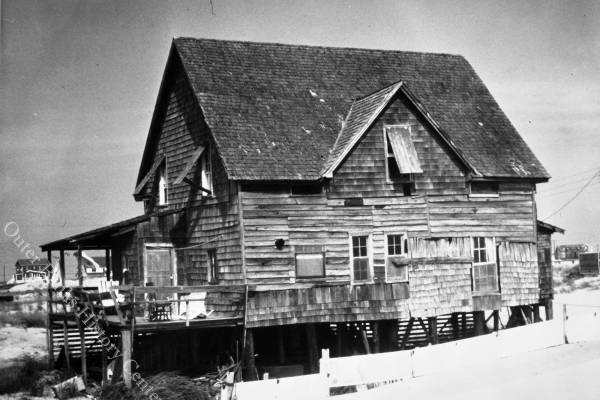

By the spring of 1988, however, the First Colony Inn was severely damaged by storms and was in a state of disrepair. Its future was threatened when the property was purchased by developer George B. Kemp of Virginia Beach, Va., who intended to construct duplexes on the site. The building was to have been burned down until the Nags Head Board of Commissioners passed an ordinance prohibiting the burning of historically significant buildings. Rather than face the expense of conventional demolition methods, Kemp offered the building to anyone who would move it off the site. After repeated efforts by various public and private organizations, a suitable location and plan were secured for the building.

Lawrence Property Management, Inc., of Lexington, North Carolina, engaged Expert House Movers of Virginia Beach, Va., to prepare the building for its move in August 1988. The building was carefully sawn into three sections and reassembled on a new 4.4 acre site three and one-half miles south of its original location. Following the move, the new owners spent three years rehabilitating the inn to the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards, selectively removing earlier inappropriate additions, repairing deteriorated features where possible, and refurbishing the interior and exterior finishes to retain the historic quality. Although relocated, the inn is situated in a setting that recalls the open, natural qualities of the original environment. The building, reopened as a bed and breakfast inn in 1991, retains its original, handsome simplicity and architectural integrity.

The American tradition of moving buildings has been going on since the Revolutionary War when the British expressed their surprise at the colonists’ propensity for moving their houses around. The notion of building relocation grew largely out of the fact that early American buildings were built of simple wood framing, were light weight, and had an integral structural system. In many instances the only way to save or protect a building is to physically move it out of harm’s way.

This approach is particularly commonplace on the Outer Banks where buildings have often led a transitory existence. The dynamic, hostile nature of the coastline can have a detrimental effect on the natural and built environment. Waves, sand, and driving storms have threatened cottages, hotels, and other businesses since they were first constructed on both the sound and ocean sides of the islands. The simple wood frame structures, typically built on wood pilings above the destructive waves and sand, were easily disconnected from their sites, picked up, and moved farther away. When ocean side development first occurred, some structures were simply relocated from the sound side. Some structures are believed to have been moved as many as four times. With this history, fewer historically significant structures exist on their original sites than those which have been moved. More than one longtime resident/vacationer (incorrectly) recollected that the First Colony Inn had been originally built on the sound and later moved to the ocean side. One hotel, The Arlington, and a portion of another hotel named Hollowell’s did experience such moves.

The overall environment of the new location is compatible with the visual appearance of the inn and compatible with the use. The majority of the surrounding buildings are residential in scale. The town-required setbacks all around the building and the placement of the building on the site ensures that future development will not encroach on the inn.

The attraction of Nags Head, the oldest seaside summer resort on the North Carolina coast, has always been its romantic and social aspects. From the early periods, when the first few families arduously trekked fifty miles from Elizabeth City to spend the summer months in rude primitive style, to the early 1930s when hotel advertisements boasted “freedom from social restraints…” Nags Head has been the chosen place for vacationing. Its popularity as a vacation playground has continued into the twentieth century, and the Outer Banks still attracts thousands of visitors a year to its mystery, charm, and relaxation.

for the latest news, local events, and much more!

© Copyright First Colony Inn. All Rights Reserved.